How Much Does Culture Shape Us?

American culture, ironically, may shape us to believe it doesn’t have much impact

Over the years I spent teaching anthropology to high school students, an interesting paradox became apparent. A large number of students started the course believing that their culture didn’t play much of a role in making them who they were. They didn’t think their values could be predicted based only upon knowing they were Americans, given that they were (or so they claimed) both so individually varied and took such an active role themselves in choosing what to value. A couple of times I had them answer a brief questionnaire about this, asking both about values and about the role of their culture in conditioning them to have such values.

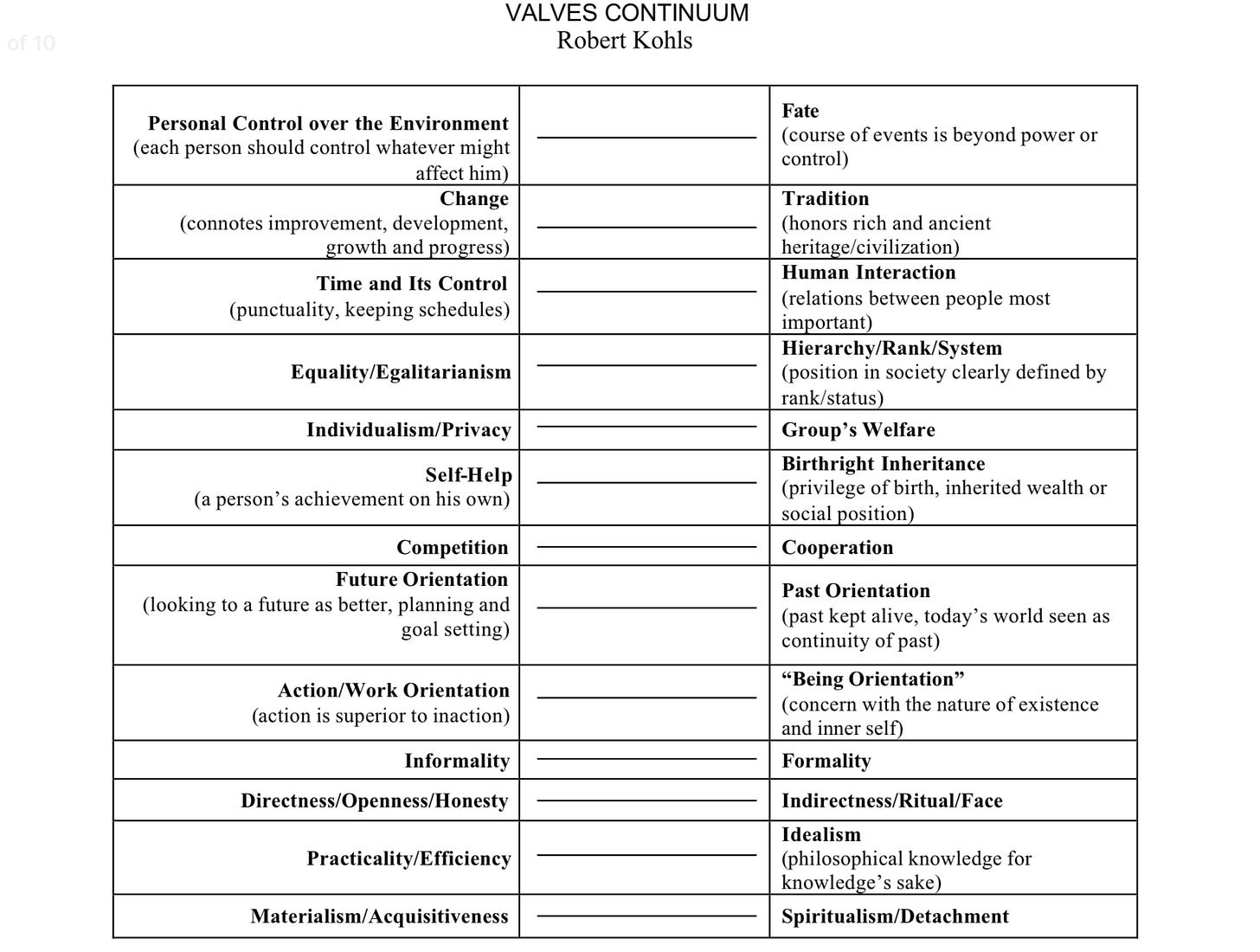

They would be a bit surprised, then, when I would then have them read an article1 about American values, written for foreign students studying in the U.S., that not only listed a set of values that matched very closely what students had chosen in my questionnaire (in pairs, such as those pictured below, with brief explanations of what each value orientation would entail), but also predicted at the start that Americans wouldn’t think it was possible to even say what “American” values are, as we are all so individual, unique, and unpredictable! So that’s the paradox - that our cultural conditioning works very effectively to get us to believe that we are such individuals of free will that we aren’t much affected by any cultural conditioning.

Put another way, one of the ways in which Americans are most alike is in how unique and unalike we believe we are. One of the most predictable things about us is that we think we are unpredictable. And one of the norms we most conform to most strongly is that we don’t think we do much conforming.

This paradox likely is even stronger and more troubling for teenagers than it is for adults, because it is amplified by being in a stage of life where the need for acceptance by peers is extremely important, while at the same time it is looked down upon socially to appear overly concerned with what others think. It’s “cool” to “be yourself” and “be real” rather than appear to be performing a role. Seeing this play out in student interactions with each other always made me feel compassion, but also happiness at not having to go through that again (although subtler versions recur throughout life).

But it also made teaching certain things in anthropology a bit more challenging. Most other societies define personhood far more socially than we do, through the roles one gets assigned due to the relationship positions one occupies in family, community, economic, and other social contexts, with how to play each of those roles far more specifically spelled out in terms of language and behavior than anything in our far less formal social roles. Initially, I think many students view these other sorts of societies as “fake” in the sense that people are not “being themselves”. This is where it became useful to make explicit the paradox of American culture raised earlier. It helped make it clear that the “real self” or “authentic individual” was much harder to define, given all people are subject to cultural conditioning to learn how to be a person in their own society. The role-playing framework is a useful one, as there appears to be a spectrum across societies (and even within them according to social situations) as to the degree of formality - a play with a script for the characters at one end, and an improvisation at the other.

Another interesting note was that I remember some students objecting to the article we read as overly critical of American values. I never saw it that way. It was written for foreigners to whom U.S. thinking would seem strange, so may have done a bit of exaggerating. However, more important was that these values are indeed outliers when it comes to the variety of cultures around the world, most of which are either further to the center or on the opposite side of the sets of values summarized on the last page of the article (below). So there was value simply in seeing how differently the same phenomenon would be understood in different cultures, as well as in seeing what would be gained as well as lost by moving toward the other end of the spectrum in any of these value pairs.

“Values Americans Live By” by L. Robert Kohls